From an automotive viewpoint, the 1970s was dominated by the fuel crisis that engulfed the first half of the decade, and the uncertain motoring outlook that ensued. Although the early 1970s would see some iconic high-performance, wedge-shaped “supercars” come to life, large engined mass-market cars suffered, out of favor for their fuel thirst and their harmful impact on the environment.

While alternative fuels, electricity in particular, were hot topics, real progress was made in the Far East, where Japan’s output of automobiles was thrifty, efficient, and affordable. They may have been scorned in Europe and the US, to begin with, but Japanese cars were also well-made, forcing Western rivals to up their game or—as some discovered—face oblivion. But it wasn’t all doom and gloom.

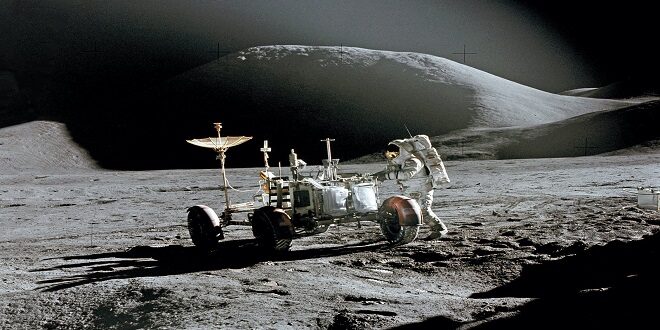

New model designs were increasingly attractive and well-equipped while, on the world’s race tracks, lateral thinking produced giant steps in aerodynamics. Engineers even developed a car that could be driven on the Moon.

Bond bug

Britain’s most parochial maker of economy cars and an Austrian-born industrial designer put this adventurous car into mass production. Reliant was Britain’s biggest three-wheeled vehicle manufacturer when, in 1963, it contracted Ogle Design—a leading product consultancy—to improve its image.

Coincidentally, Ogle’s managing director Tom Karen had planned his own tiny three-wheeled fun car, called the Rascal, back in 1958. Aimed at students, it was designed to be cheap to make and own. At first, Karen was occupied with Reliant’s innovative Scimitar GTE sports-station wagon, but by 1967 his client was eager to add his sporty three-wheeler to its line-up.

The final production car was amazingly faithful to Karen’s proposal, including the vertically truncated tail, the exposed rear axle, and even a plywood trunk lid. Reliant insisted on more luggage space within the plastic body but actually made the car more radical by incorporating a lift-up canopy with side screens, instead of a fixed roof.

The car went on sale in June 1970 as the Bond Bug, the Bond marque having been acquired by Reliant that year. It could be bought with Reliant’s “credit package” offering time purchase, a two-year warranty, and cheap insurance, designed to foster sales among young drivers.

It was quite exhilarating to drive despite its meager power, yet the Bug was a small seller and was dropped in 1974, unable to overcome the Mini’s four-wheeled allure.

Citroën sm

Citroën had long plotted a genuine flagship model mixing the DS’s high-tech logic with two extra facets: performance and prestige. Therefore, the opportunity to buy Italy’s Maserati in 1968 proved ideal for adding the supercar experience to Citroën’s renowned design ideals.

The result, in 1970, was the fabulous Citroën SM, a stunning combination of French ingenuity and Italian panache. At its heart was a tidy 90-degree V6 Maserati engine, derived from the marque’s V8.

Costin amigo

Frank Costin was an eccentric, chainsmoking engineer whose mastery of aerodynamics—gleaned in the aircraft industry—made him a godsend to racing teams like Lotus and Vanwall in the 1950s.

He became the “-cos” part of sports car firm Marcos with partner Jem Marsh; his aeronautical engineering expertise led him to take the unusual step of using laminated marine plywood for the chassis of his first cars, to minimize weight.

Sommer joker

The car world went beach buggy crazy in the late 1960s, inspired by California’s surf culture. A “different” contribution from cold, remote Denmark might have been expected, and the Joker didn’t disappoint.

Last word

It came from the fertile mind of Danish car distributor Olé Sommer, who intended to offer a none-too-serious car that could be practical in the wild. His Joker rode on a stout box-section separate chassis on which an external framework of hot-dip galvanized steel pipes acted as the body frame.

Magazine Today

Magazine Today